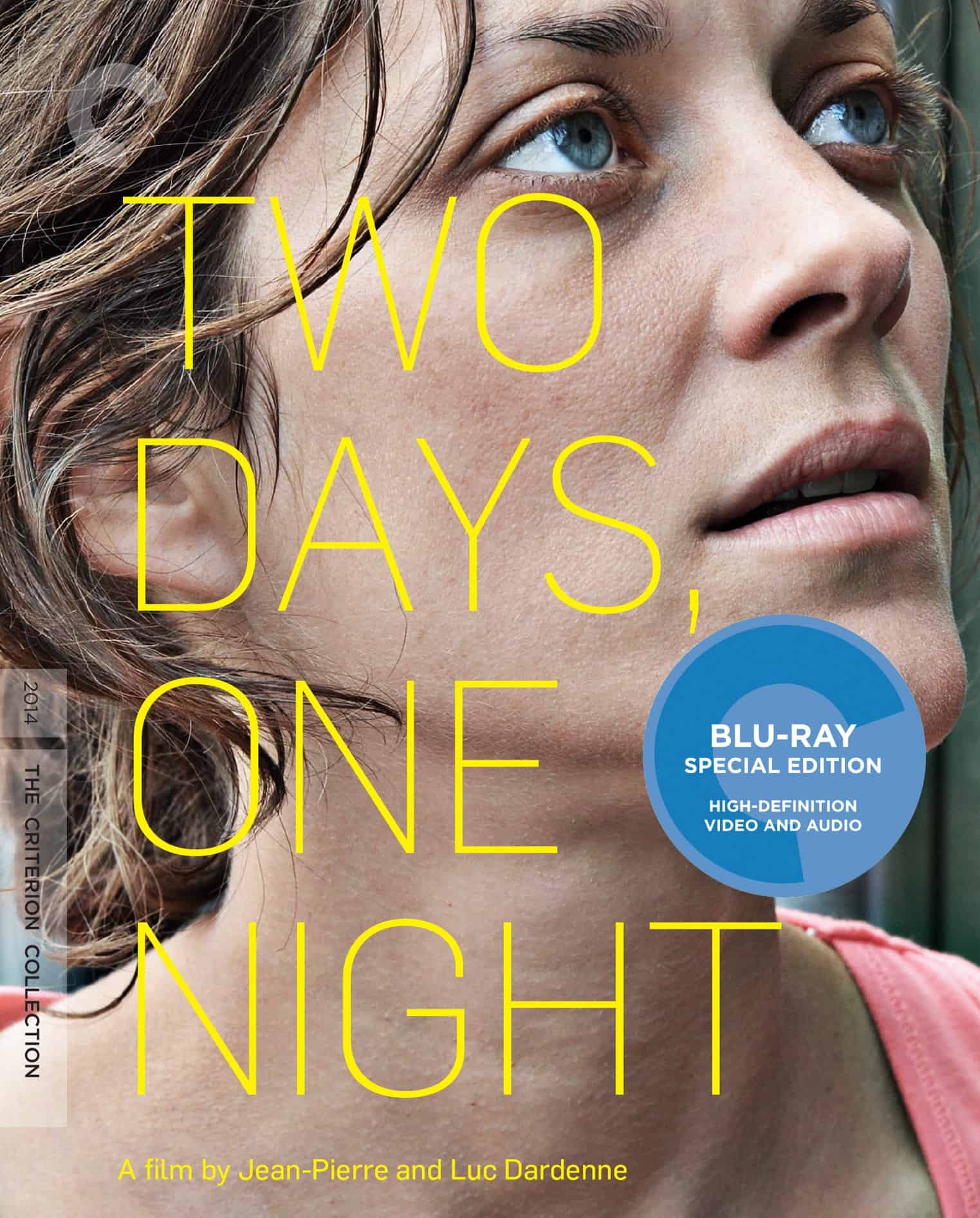

Are there any filmmakers working today with a better recent track record than Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne? From their 1996 feature La Promesse, to Two Days, One Night (2014), available now on a new Criterion Collection Blu-ray, the writing/directing duo have made seven classics of contemporary world cinema in a row, all of which were also among the best of their respective year of release. There have been six films up for the Palme d’Or, resulting in two wins (as well as five other Cannes awards), five César nominations, a host of critical accolades, and dozens of other honors spanning the globe (though curiously, no Oscar love for the brothers). Two Days, One Night, itself the winner of 40 international awards, is just the latest to follow this exceptional trend. It’s a film utterly unique in so many ways, yet perfectly consistent with the Dardenne filmography.

Teaming with Marion Cotillard, who did receive an Oscar nomination for her role in Two Days, One Night, the Dardennes were collaborating with their highest profile star to date. But as is their tradition, they maintain a low-key approach toward style and storytelling, with an unobtrusive aesthetic, a limited location, a narrow time-span, and a narrative that is powerfully intimate, universally relevant, and sometimes painfully honest. This time, the plot follows Sandra Bya (Cotillard) over the course of a weekend, as she seeks to persuade her 16 coworkers to support her keeping her job rather than them receiving a bonus. While Sandra was on medical leave, the supervisor of her solar panel factory decided the crew got by just fine without her, thus rendering her position unnecessary. In her absence, a vote was held to either have the company pay to keep her job, or pay each of the other employees an annual bonus for some additional work. Following the 13-3 decision in favor of the bonus, Sandra makes her rounds, often with her husband, Manu (Fabrizio Rongione), attempting to sway opinions before a Monday-morning recount. Despite its absence of conventionally suspenseful tropes, as Girish Shambu describes it in his essay, “Two Days, One Night: Economics Is Emotion,” the film is, nevertheless, “a model of that familiar form, the ‘ticking-clock thriller.'”

The solar panel business here is an operation just small enough for close relationships with coworkers to be casually developed, which subsequently leads to complex personal motivations and feelings regarding the decision. At the same time, it is also just small enough that divisions can easily breed animosity. (And as the brothers point out in an interview on the Criterion disc, such a business is also just small enough to avoid unionization, which presumably would have restricted such a ballot-based procedure.) As with most of the Dardennes’ work, there is a singular focus of narrative attention, a primary 1-3 characters or so who are so prominent, so dynamic, and are usually performed with such complete conviction that it is often easy to overlook the larger issues at hand. This is somewhat the case with Two Days, One Night, where the socioeconomic themes are clear and present yet are also rather secondary. Though Shambu does make a strong case for the film as an examination of the post-2008 financial crisis and a concurrent capitalistic critique: “Like all of their films of the past two decades, Two Days, One Night feels urgent and jolting because it holds a mirror up to life lived in our current global economic regime. And this time around, the picture they paint acquires a redoubled resonance in the ongoing aftermath of the financial crisis.”

Still, such issues may drive the narrative and give Sandra her motivation (and give the film its wider cultural relevance), but her personal drama as a result of this catalyst overshadows what started it all in the first place. Luc Dardenne talks of the film as depicting the “solitude of the worker,” insofar as it illustrates the isolation of a lone figure within the larger framework of a corporate mechanism, and while he is undoubtedly right about that, such a statement also speaks to the way the Dardenne brothers’ films can hone in on individuals, and individual concerns, which may otherwise be buried or ignored within a larger social construct.

Solidarity is another of the ever-present themes that run throughout the Dardennes’ work. It takes on various guises—as in families sticking together, friends uniting, lovers bonding, etc.—but here the emphasis is on a professional solidarity. It works two ways though. On the one hand, it is, at the most obvious, about standing with a colleague, coming to his or her defense and aid. But it is also about the simple act of understanding. And even that has two branches of action. First, it is about Sandra’s coworkers, whom she pleads with for their understanding of her struggle. Second, it is also about her own evolution of discovery when seeing where they are all coming from, especially those who are reluctant to give up their bonus as a result of their own financial dependency. Having the shoe on the other foot isn’t always easy, but it is usually enlightening.

Again like those in so many Dardenne films, Sandra subsequently undergoes a life-changing journey in a matter of hours, and grows immensely in her transformation from weakness to strength. It doesn’t always look good for the young woman, most evidently as the tightly restricted interiors intensify and accentuate her psychological instability (she is nearly always on the precipice of a complete and devastating breakdown, coming mortally close at one point), but there is an underlying perseverance that keeps her efforts tinged with optimism.

Giving emotional credence to the representation of various intertwined lives and their specific scenarios are the actors in Two Days, One Night, all of whom are excellent. Cotillard is certainly the heart of the film, and hers is a powerhouse performance, one of her best, but the supporting cast is also brilliant, broadening the scope of the picture to illuminate those on the periphery of Sandra’s plight. Each supporting player does a remarkable job bringing his or her character to life despite minimal screen time, which results in not only Cotillard having extremely capable counterparts, but also adds to the viewer’s sympathy for even those who decline Sandra’s appeal.

In a nearly hour-long Criterion conversation with the Dardenne brothers, it becomes clear, in a way, just why their films are so special. First and foremost is their methodical direction, and they insightfully elaborate on their careful attention to the staging of characters within their setting, the placement of props, and their choice of camera angles, distance, and movement. I say “in a way,” however, because despite these explicitly voiced explanations of technical practice, it all still seems so deceptively naturalistic. Even with an extensive rehearsal period (five weeks according to Cotillard, who says the time is integral to the rhythm and authenticity of the film), nothing at any time appears contrived. “Organic” is a word that comes up often in the Criterion interviews, as the brothers and their actors speak of character actions and traits naturally occurring during these rehearsals or the actual shooting. And as is pointed out by Rongione, who has himself appeared in five Dardenne films, many incorrectly assume those appearing in the brothers’ movies are amateurs, which further suggests a truthful quality one generally attributes to non-actors.

Assisting this fundamental creation is the fact that especially in Two Days, One Night the Dardennes frequently compose in sequence shots, where a single take follows characters in close proximity, recording the good and the bad, the exciting and the banal, all the drama and action, or lack thereof, as it steadily, realistically unspools. In this formal design is the tension of the everyday. Shambu cites Dave Kehr, who writes, “Though the Dardennes’ films are scrupulously naturalistic, they all belong to the suspense genre, though it is a suspense of character, not of plot. It is not so much a question of what will happen next as of how the characters arrive, or fail to arrive, at a decision to act.” By not cutting, by not drawing back during times of potential distress, the brothers ratchet up the anxiety with the certainty that we will bare witness to whatever the characters decide to do, or not do.

For directors who have such a uniquely consistent worldview and filmmaking style, several of the bonus features on the Criterion disc allude to a surprising number of multimedia influences. The brothers alone draw a connection between their films and reality television, they pay homage to Satyajit Ray’s The Big City (1963), and they profess an admiration of Cesare Zavattini’s Neorealist ideals (this is where the sequence shots come into play). And in his visual essay, Kent Jones refers to Eisenstein and Rossellini when discussing the Dardenne brothers and their cinematic points of reference. With Two Days, One Night in particular, I would also say there is also something of 12 Angry Men (1957) in its essential narrative construction, in that both films follow the efforts of one as they try to convince and sway others.

But perhaps the most astute comparison is when Jones cues up a statement by Jean Renoir. Remember it was Renoir who uttered his often-quoted quip from The Rules of the Game (1939)—”Everybody has their reasons”—which itself is apt when it comes to the cinema of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. In this case, though, Jones brings in another quote from the famed French filmmaker, one that similarly gets to the crux of the brothers and their work, and hints at why their films are so powerful and so full of captivating energy. It comes down to reality, and reality, says Renoir, “is always magic.”

No comments:

Post a Comment