Depending on where one draws the line in his filmography, Fellini’s Casanova may be the best film of Federico Fellini’s late period (I would argue it ushers in that era). Of any period, it’s certainly one of his most underrated. It was, according to Fellini biographer John Baxter, the most complex project of the director’s career, ultimately costing $10 million, making it also the most expensive.

Though a commercial failure, which greatly disappointed Fellini, Casanova follows a thematic line extending throughout the maestro’s 40-years of filmmaking. From the drifting layabouts of I Vitelloni (1953) to the hollow wanderings and shallow encounters of Marcello in La Dolce Vita (1960), to Donald Sutherland’s titular role in this 1976 feature, Fellini’s focus on an alienated, superficial existence repeatedly found new and unique manifestations. Such a pattern continues here, as the legendary Casanova emerges to be a lonely figure, one who fancies himself a “man of letters” and yet is nevertheless known only for his ability to have sex … really well, apparently.

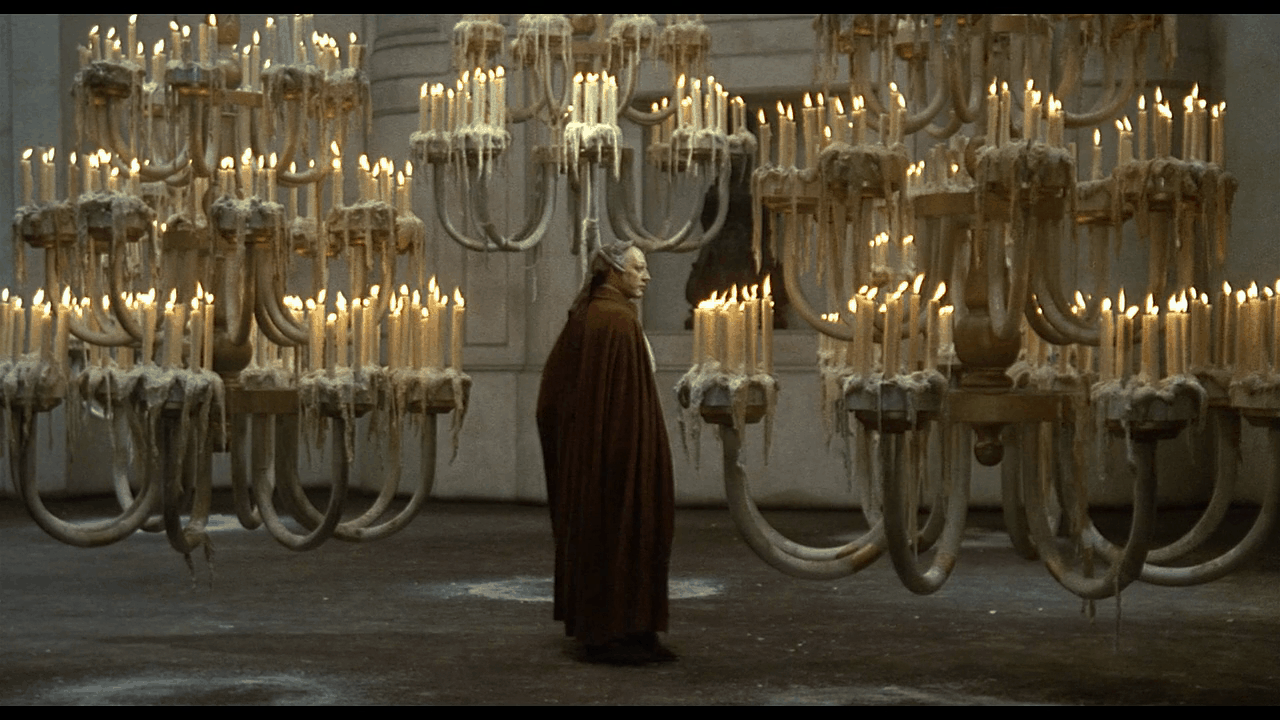

Fellini’s Casanova is very loosely based on Giacomo Casanova’s autobiography (as much as any Fellini film could ever be based on anything), and it opens in the midst of a celebratory carnival, a frenzied gathering that bursts with lights, color, fire, spectacle, music (or rather, sounds), and a horde of clamoring people. Early on, we see Fellini’s representation of this world is going to be a largely fabricated and exaggerated one, where over the top is just the beginning. The fantastically illusory nature of the film is made evident in such setting details as illuminated plastic bag ripples standing in for water waves and, later, some obviously staged stationary shots of supposed vehicular mobility. With this combination of pageantry and artificiality, Fellini’s film plays out as each passing scene maintains a continued preoccupation with performance and deception.

It seems Fellini’s depiction of Casanova was to be far more scathing than it finally became. Indeed, it is now quite the opposite. While he isn’t exactly an admirable figure, and Fellini frequently voiced a dislike of his behavior and his ego, Casanova is an unexpectedly tragic one. Given the film’s source and subject, sex is predictably prevalent, from graphically illustrative murals to wardrobe replete with suggestive, and quite sexually accommodating, attire. Yet as Casanova travels country to country, embarking on what is essentially an episodic series of sexual escapades, he continually likes to profess his wit and his cunning, and he would rather speak of his wealth and his experience in commerce than his prodigious sexual abilities. But while he is touting his intellectual accomplishments, others couldn’t care less. They just want to see him do it. He even attempts to intellectualize his sexual prowess, discussing the various scientific reasons why he performs better than others do. Nobody cares. His amorous reputation precedes him wherever he goes, and it far outweighs his own philosophical pronouncements. Everyone sees his proficiency merely as grounds for a contest of sexual stamina. Who cares about the why or the how? In the end, his experiences are ultimately empty (like Marcello and the boys from I Vitelloni), so much so that one of his most satisfying sexual encounters is with an automaton.

Now this is not to say Casanova doesn’t like sex. As frivolous as parts of his life are, he does at least appear to approach sex with a genuine verve and passion. When it is time to get busy, he does so with a wild abandon, frequently accompanied by the bleep, bleep, bleep of some sort of phallic mechanical bird contraption somehow connected to his lovemaking. And that bird is just one element of what are some of the most bizarre sex scenes ever committed to celluloid. Notably though, these sex scenes are ridiculously hysterical, clearly synthetic, and not the least bit arousing (curiously, there is also little to no nudity). So again, there is this combination of showmanship and simulation.

Despite some initial difficulties while shooting (as much a result of the language barrier as Fellini’s unorthodox directing style), Sutherland shows quite the range here, going from the flamboyantly extreme, carousing with great gusto, to the potently somber, as he expresses apparent disillusionment and silently reflects during moments of pause. Two things appear to affect Casanova most. First, while he clearly loves women in general, and has no trouble making love to all sorts, his trouble is finding that one single woman to love. For all his trysts, he lacks the capacity to form a durable relationship. Second, while he does meet diverse political and social figures through the course of his travels, he winds up looking for sophistication in all the wrong places. In many of the locations where he ends up, he finds only debauchery, chaos, and foolishness, and is almost always intellectually dissatisfied, if not physically.

Fellini’s Casanova concludes with a dream sequence, which though certainly peculiar is really nothing so very out of the ordinary within the context of the film, where the entirety of the picture to this point likewise took the form of a surreal exhibition. The ending is, however, a rather beautiful and peaceful conclusion to what had otherwise been a generally manic adventure.

In typically ambiguous fashion, Fellini has called the film the worst he ever made, yet he also stated it seems to be his “most complete, expressive, [and] courageous.” It would make sense that Fellini cared a great deal for the film. There are times when it truly feels like his invigorating life force seeped into the production and reveals itself in the finished product. A giddy vibrancy runs throughout the movie, as if he reached into his distinctive bag of cinematic tricks and pulled out his entire arsenal. If Fellini’s Casanova does lag at times, as during Casanova’s brief stopover in Switzerland, the slower moments only really stand out in comparison to the vitality of the surrounding sequences; on their own, or in another film, there would be nothing so terribly sluggish about these more sedate moments.

Fellini’s Casanova contains an unmistakably Fellini blend of the fantastical and the grotesque, all enhanced by frequent cinematographic, editorial, and musical collaborators (Giuseppe Rotunno, Ruggero Mastroianni, and Nino Rota, respectively). Amazingly, Fellini’s script, written with Bernardino Zapponi (who had just the year prior penned Dario Argento’s fabulous Deep Red), was even nominated for an Academy Award. Populating the picture are classic Fellini characters and caricatures, his “landscape of faces,” all mixing and mingling in an eccentric concoction of abnormal bodies and faces and perverse behavior. Moreover, as with several of his films, particularly during the years around Fellini’s Casanova, there is also the inventive costume design further endowing these individuals with their striking presence (Danilo Donati won an Oscar for his creative outfitting). Taken together, Fellini orchestrates a visual delight of eccentric individuals, vibrant colors, shifting light design, and a detailed, expansive, and astonishingly complex set construction, all at the renowned Cinecittà studios, by now well-tread ground for Fellini.

Fellini’s Casanova boasts an assortment of people, locations, and entire sequences that are created and realized in a way that can only be called “Felliniesque.” Clichéd though it may be, there is simply no other adequate description.

The post is written in very a good manner and it contains many useful information for me.

ReplyDeleteWall Lights