‘The Brood’

Inspired by his own unpleasant divorce, and the subsequent liberation of his daughter just before his ex-wife was able to take the girl to a California cult, David Cronenberg’s The Brood is essentially an ugly, highly unorthodox custody battle. As the great Canadian filmmaker famously quipped, “The Brood is my version of Kramer vs. Kramer [also released in 1979], but more realistic.”

The Brood is Cronenberg’s sixth feature, coming just after the seemingly out of place Fast Company (1979)—not so very odd given the director’s love for automobile racing—and just before his more exemplary breakthrough, Scanners (1981). It is consummate Cronenberg, with a heady mixture of clinically twisted science and the deep psychological strain that inevitably mars said science with corporeal disfigurement.

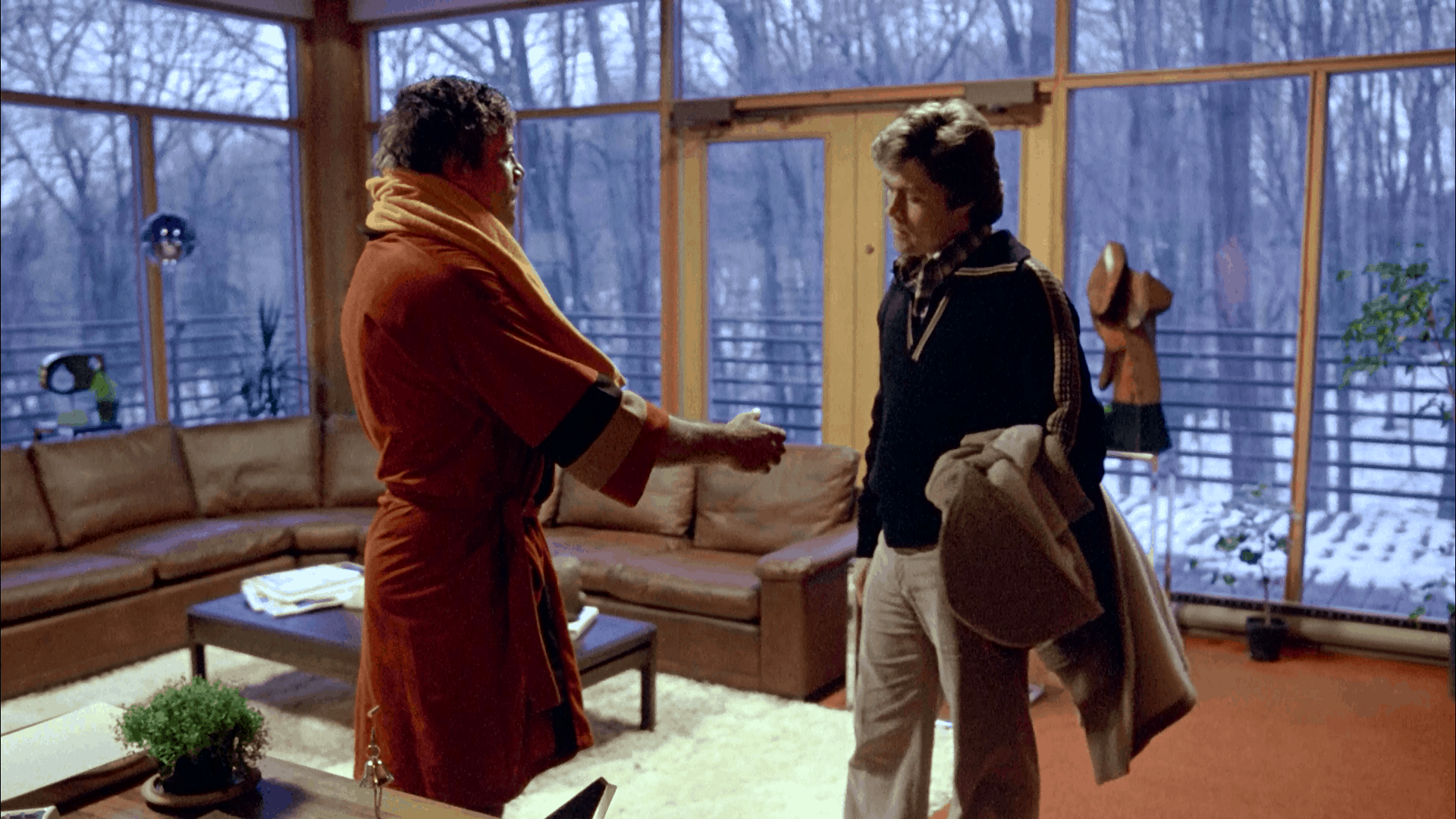

With his wife, Nola (Samantha Eggar), undergoing treatment at a facility known as the Somafree Institute of Psychoplasmics (a Cronenbergian term if there ever was one), Frank Carveth (Art Hindle) discovers his daughter, Candice (Cindy Hinds), is returning from visitations with her mother bruised and scarred. Given his estranged wife’s instability, as well as the dubious nature of the institute, Frank naturally assumes Nola is behind the abuse. She is in therapy of some sort, under the psychiatric care of the unconventional Dr. Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed), author of “The Shape of Rage.” It is clear there is more than a doctor/patient association with Raglan and Nola; it would seem there is more than even a sexual male/female relationship. There is something far more devious at play.

It is suggested Nola may have suffered past abuse at the hands of her own mother, Juliana Kelly (Nuala Fitzgerald), who tells Candice her mom would sometimes wake up covered in big, ugly bumps when she was little. Was Juliana then, or is she perhaps now, a partial catalyst for the bizarre events that transpire? Certainly, some type of hereditary malice is presumed, something even more pronounced by the film’s end. Perhaps invoking his own personal concerns at the time, Cronenberg appears to posit that women in general, from one to the next, possess the capacity for manipulation and destruction. “Mommies don’t hurt their own children,” says Nola at one point, quickly adding that maybe sometimes they do. This is not to suggest any type of misogyny on Cronenberg’s part, though many have. As Carrie Rickey points out in her essay, “The Brood: Separation Trials,” “In the judgment of film historian Robin Wood, his most outspoken critic, Cronenberg consistently exhibited his dread of women by creating monstrous, voracious, and repellent female characters.” While this may go to the extreme, phrases such as Raglan’s declaration that, “The law believes in motherhood,” singe with bitterness, no doubt stemming from Cronenberg’s own predicament.

Nevertheless, just as suspicions are aroused concerning Juliana’s potential culpability, she is brutally attacked. It’s not clear by who, or what, but the assailant is a little child-sized creature emitting ferociously guttural growls. For a time, The Brood then takes on the basic form of a police procedural, as an investigation into the murder ensues. But things change when Frank hears testimony and sees evidence of the physiological damage inflicted at the hands of Raglan and his disreputable procedures. According to one tormented patient, the doctor encouraged his own body to revolt against him through a type of mind control, a mentally induced malevolence.

Nola’s father, Barton Kelly (Henry Beckman) enters the picture and briefly brings with him his own emotional baggage—he has been separated from the departed Juliana for some time (marital troubles run rampant on screen and off). And Candice’s teacher, Ruth (Susan Hogan), likewise gets unknowingly involved, even though she makes an effort to remove herself from the situation, telling Frank his life is “just a little too complicated.” She has no idea.

As the film proceeds, and recalling Raglan’s famous text noted above, it becomes evident just what shape Nola’s rage can indeed form, as she produce the literal, physical manifestation of her anger. The Brood expresses a perfect Cronenberg union of the psychological and the physical, a conglomeration that generates any number of gruesome effects, primarily, in this case, the gestation of Nola’s organic spawn, little people called at various times “deformed children,” “monsters,” or, most portentously of all, the “disturbed kids in the work shed.”

As part of a documentary included on the newly released Criterion Collection Blu-ray of The Brood, Eggar says the part of Nola was “Shakespearian,” and hers is definitely the standout performance of the film. She is mostly seen seated, in the same setting, in basically the same position. Yet within this physical constraint, she demonstrates an oftentimes hysterical range of emotion. When Nola is referred to as the “queen bee,” it’s an acute analogy to what exactly her maternal role has involved. The reveal at the end of the film, and what follows, is a classically creepy Cronenberg climax that ranks among his most intensely shocking and brilliantly realized.

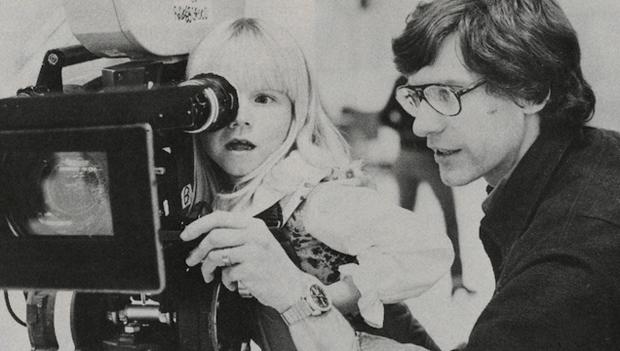

The others featured in this documentary, including producer Pierre David, cinematographer Mark Irwin, assistant director John Board, and makeup effects artists Rick Baker and Joe Blasco, all spend a fair amount of time quite rightly touting the exceptional artisanal effects of The Brood and other Cronenberg films, the make-up, prosthetics, and puppet designs that distinguish much of his early work. They also speak of the film in terms of its unique standing as a Canadian production. To hear these individuals discuss such an isolated and insular film industry truly does emphasize just what a phenomenal jolt of distinctive creativity Cronenberg was (and still is).

Irwin also hits on something else that comes through in many of Cronenberg’s films, but especially so with The Brood, and that is the oscillation between brightness and darkness to create suspense. As he points out, it is one thing to go from a reasonably dark location to an only somewhat darker site; the horror is there in the visual shift, though markedly less evident. But to go from someplace bright and clear into the darkness—literally and figuratively—makes the effect more pronounced. With The Brood, part of what gives certain scenes an unsettling undercurrent, resulting in a thematic continuation of domesticity torn asunder, is that well-lit, impeccably homey interiors, all ensconced in wintertime tranquility, can breed the most hostile actions. After Juliana is attacked, an officer suggests the assailant may have been in the house all the time, the implication being that home is where the horror is.

Cronenberg’s sophomore effort Crimes of the Future (1970) is also included on the Criterion release. While the availability of this generally obscure title is a major plus, and is an excellent addition to what is already a well-stocked disc, the film itself is not very good, though it is apropos to the themes of The Brood. If not for what is necessarily seen, much of what is discussed in this early feature does reemerge in later Cronenberg titles. Making up the rest of the disc is a delightfully informal interview with Hindle and Hinds conducted by Fangoria editor in chief Chris Alexander, and a 1980 episode of The Merv Griffin Show, featuring the notoriously rambunctious Reed, a rotund and ever captivating Orson Welles, and Charo, who mostly just leaves the three men baffled.

Couple the recurrent Cronenberg motif of transformative physiological processes with the director’s private demons at the time of production, and the offspring is The Brood, one of his finest films. It is a stunning testament to Cronenberg’s ability to allegorically expose and explore real world traumas, such as death and divorce, via an extraordinarily unique vision. One thing also remains certain: children’s snowsuits never looked so menacing.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment