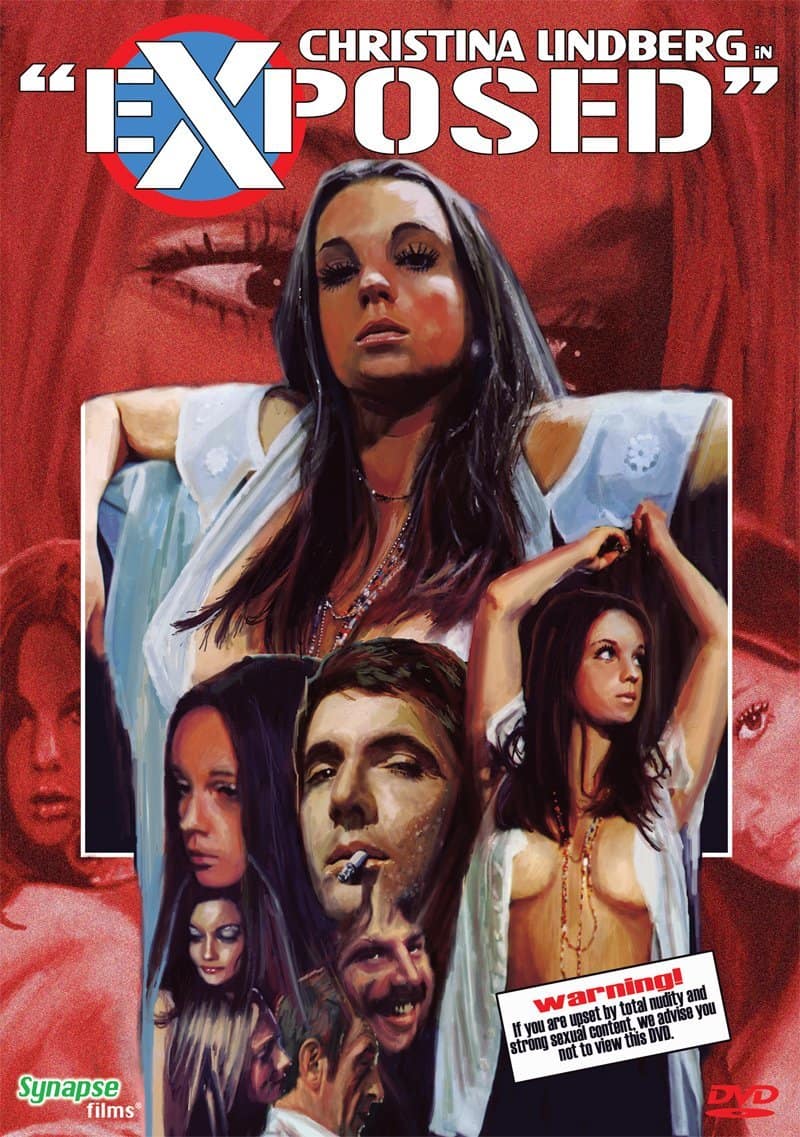

It all started with

Exposed.

I’m not sure what brought this 1971 Swedish sexploitation film to the

suggestion portion of my Netflix account (presumably the roster of Jess

Franco films recently added), but after reading the description, I

figured it was worth a shot: “A pretty young teen finds her innocence

lost when an unguarded night of revelry yields shameful secrets, and a

stack of nude pictures that could ruin her life. But to get her hands on

the negatives, she’ll have to expose herself even further.” That is

indeed the basic plot of the film, which plays out exactly as one would

expect for such fare. But what was unexpected while watching

Exposed (also known as the much less enticing

Diary of a Rape), was the 21-year-old star of the film. Her name is Christina Lindberg.

Exposed, for lack of a better phrase, is what it is. It

delivers on everything its suggestive promotional material promises,

namely nudity. While not exactly enraptured by its narrative (though I

have certainly seen many a more flimsy premise), I nevertheless came

away absolutely infatuated. Not by the story, not by the genre, not by

the era or country in which the film was made. It was this Christina

Lindberg. Now of course, I must confess she is a knockout, a stunning

beauty who combines the most erotic of allure with the most innocent of

charms. Yet there is something more. Those who are familiar with

Lindberg only in passing may dismiss this, knowing her simply as the

often-nude sexpot—looking back on these films, she said she had a

“natural way to cope with no clothes”—but there is genuinely something

captivating in her performance. Her presence frequently gave even the

most sub-standard film a surprising degree of watchablity.

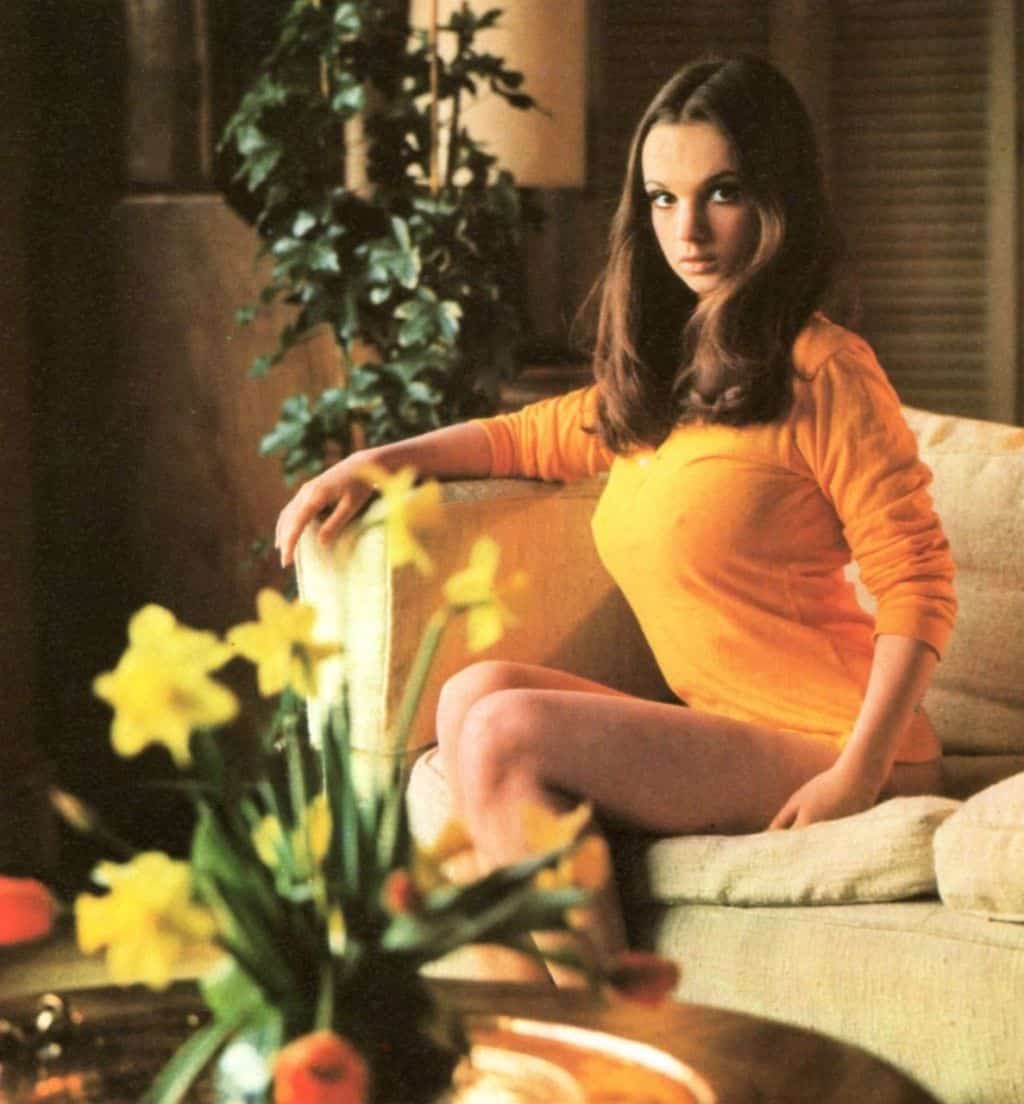

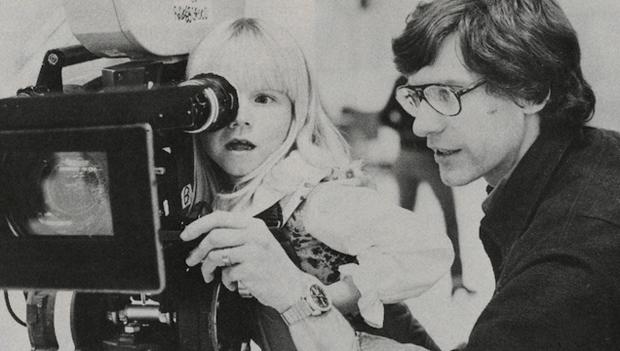

Lindberg was born Dec. 6 1950 in Gothenburg, Sweden. She began

modeling in the late 1960s, while still in high school, first in

publications relatively innocuous, then in the more scandalous likes of

Playboy, Penthouse, and others. This led to her first acting role in

Maid in Sweden (1971), also while she was still in school (though she was 18), followed by

Rötmånad (AKA

Dog Days and

What Are You Doing After the Orgy?, 1970),

which was actually released prior to her debut. About two dozen films

followed, 17 just in the 1970s, and six released in 1973 alone. While

some of the movies were barely better than atrocious, when Christina

Lindberg appears, all is forgiven.

As a whole,

Maid in Sweden

isn’t bad. It’s a standard coming of age tale (a premise that figured

into many similar sexploitation movies), and as such, it gives Lindberg a

chance to play up her expressive naiveté. Anyone familiar with Lindberg

and her film or modeling work would probably find it amusing that she

plays a chaste young girl unwise in the ways of sex, but that was, of

course, the point: all the better to make her sexual awakening that much

more, well, sexual. In one of several English-speaking roles, the

pig-tailed Lindberg plays bewildered timidity extremely well.

Ironically, though befitting the youthful lark’s titillating aspiration,

Maid in Sweden takes her innocence and packages it in the most

suggestive of apparel, as when on a date she wears a white dress that

is comically revealing given her supposed purity (the evening ends with a

sexual assault that strangely leads to mini-romance).

Maid in Sweden has several similar scenes that display the

dual nature of Lindberg’s recurring screen persona. One prolonged

sequence, for example, has her Inga character masturbating to the sounds

of her sister and her boyfriend having sex (played by real life husband

and wife Krister and Monica Ekman). The next scene then has the trio

merrily ice skating, with Lindberg looking like a wounded puppy when she

is tripped up. This back-to-back balance of blatant sexuality and

childlike disorientation is an exemplary Lindberg trait. Off screen, she

herself embodied this juxtaposition of being withdrawn and flamboyant.

“I was very shy,” she has stated. “I was very shy and it seems a little

bit odd when I take off my clothes and such, but I was very shy.”

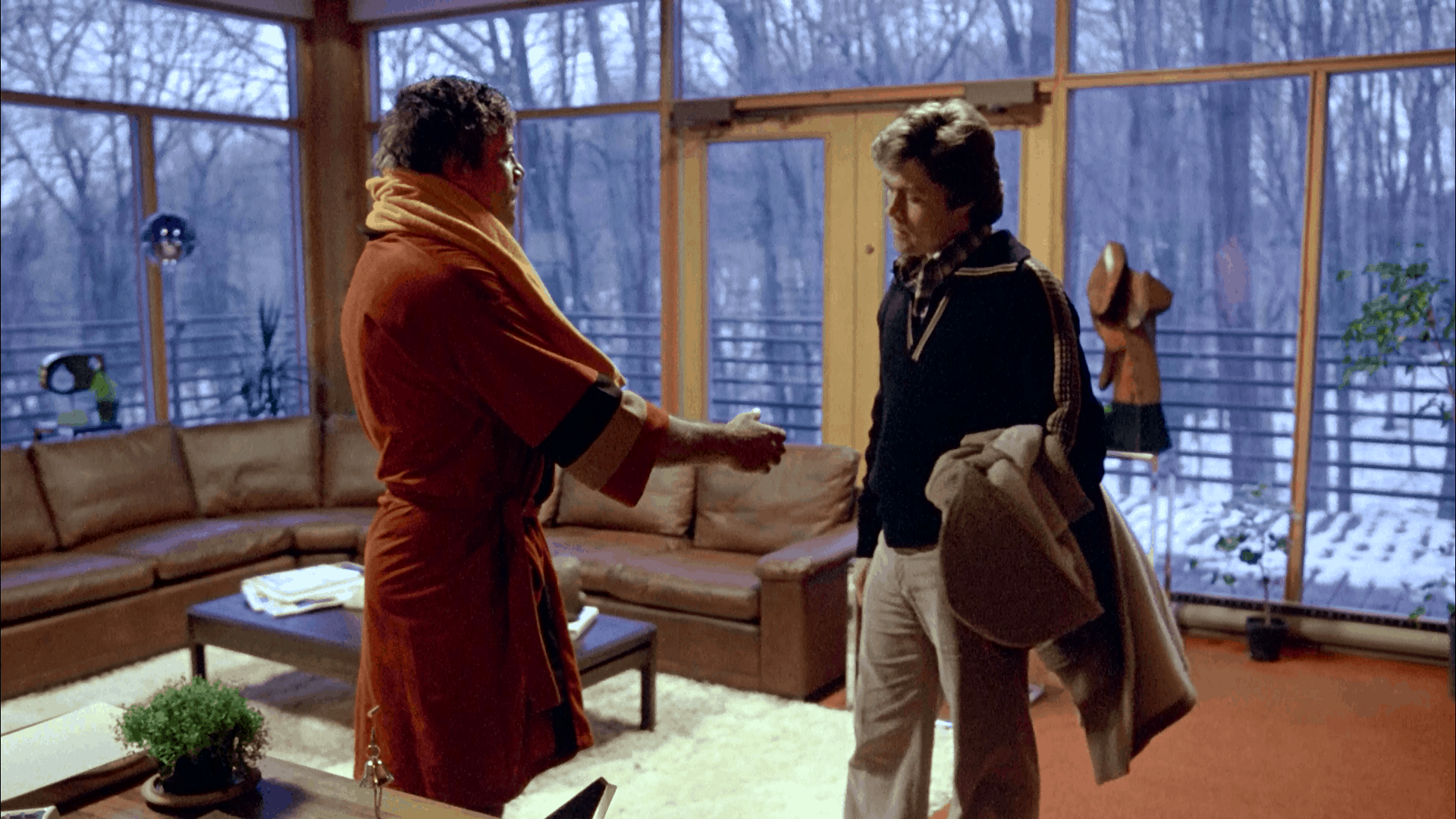

Just after

Maid in Sweden, Lindberg worked with the (in)famous American director Joseph Sarno on two films. She hardly appears in

Swedish Wildcats (1972), but she is far more prominent in

Young Playthings (1972),

where she hardly appears clothed. In this rather odd film, her

character, Gunilla, is unknowingly being primed for a threesome

consisting of her, her boyfriend, and her best friend (the latter two of

whom have already been having an affair). Gunilla, however, becomes far

more intrigued by a woman who collects and repairs old toys. This

woman, as Gunilla soon finds out, also hosts elaborate costume parties

where attendees don make-up and various outfits then act out a variety

of erotic folk tales…or something to that effect. Either way, while it

takes some work to coerce Gunilla into the ménage à trois, her initial

reticence toward that, and the sexually charged routines, is quickly

lessened. Echoing the above point about thematic virtue in order to

stress the sexuality, at one point she bashfully states, “I’m much too

self-conscious.” This despite the fact she is frequently and unashamedly

nude throughout the film.

While not the star of the show, Lindberg has a supremely notable role in

Sex and Fury (1973),

where she plays opposite the first-billed Reiko Ike, quite the

sexploitation icon herself. Overall, this might be the best film to

feature Lindberg. Some may make a case for the cult classic

Thriller

(more on that later), but if one looks strictly for an interesting

story, decent action, stylistic dynamism, better than average production

values, and yes, sex, this hits more high notes than most. Even with

Lindberg in a secondary role, her appearance is intoxicating. The film

has one of her best entrances, as she descends a lavish staircase under

spotlight, her face partly concealed by a mask, which she then removes

to dramatic effect.

Sex and Fury is a wildly entertaining conglomeration of

glorious bloodletting, a decently engaging revenge plot, political

corruption and social upheaval, knife-wielding nuns, Lindberg dressed

like Pocahontas whipping Reiko (seriously), fighting, nakedness, and

nakedness while fighting. Lindberg’s character, an English woman fluent

in Japanese—played by a Swede—is likewise a multifaceted individual. She

is a sharp-shooting, ace gambler who has taken on the occupation of

British secret agent in order to see her Japanese boyfriend. And of

course, she often has to sleep with both men and women in order to

sustain her cover. Still, while hers is not the primary story of the

film, her romantic subplot is actually quite touching, a rarity in her

work.

Making the most of her Japanese stopover, Lindberg followed

Sex and Fury with

The Kyoto Connection (1973). Like

Dog Days, this is a Lindberg film I have so far only been able to view sans subtitles. Unlike

Dog Days,

the story here is pretty straightforward, negating any need for

explanatory dialogue anyway. Lindberg’s character arrives in Japan and

is abruptly kidnapped, raped, and held hostage. Through her sexual

wiles, which need no translation, she eventually manages to break fee.

That’s about it.

Though her films by no means count as “roughies,” certainly not in

the pornographic sense, Lindberg, for whatever reason, often found

herself on the brutal end of various physical encounters. Even in

Maid in Sweden,

her very first film, Lindberg’s character suffers the fate of

degradation, there at the hands of her sister’s boyfriend, who mocks her

backwardness but nevertheless pounces on her in the bathtub before the

film’s conclusion. Lindberg acknowledges this as something of a theme in

her work—the beautiful innocent girl abused in one way or another. Not

really looking Swedish, the small, dark-haired Lindberg had an

international appeal, so as for the recurrence of this harsh scenario,

she attributes the frequency to the intercontinental financing of her

films. Similar themes and characters were desired as producers from

around the world put up money on the basis of a specific type of

repeated character in a specific situation, however brutal it may be.

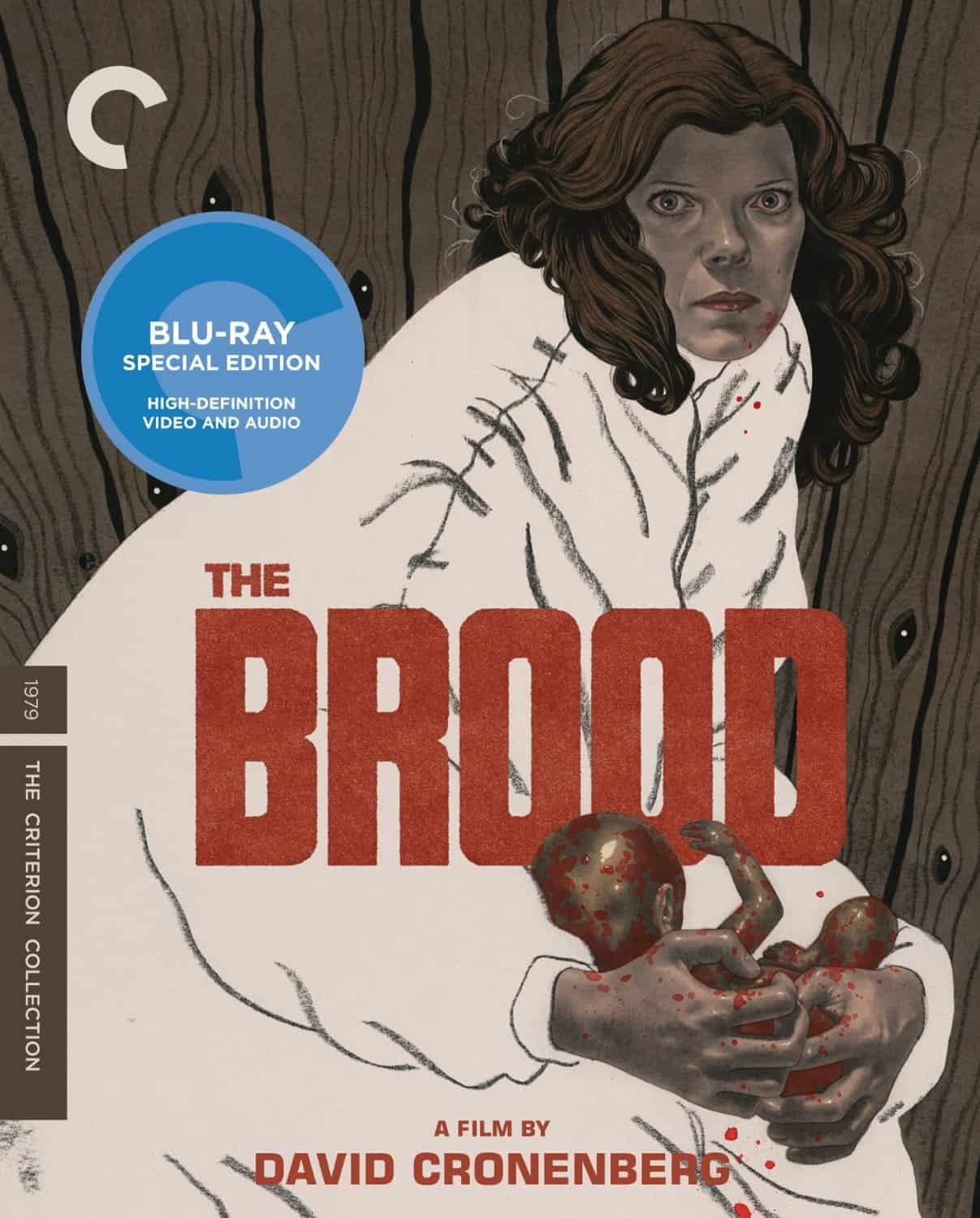

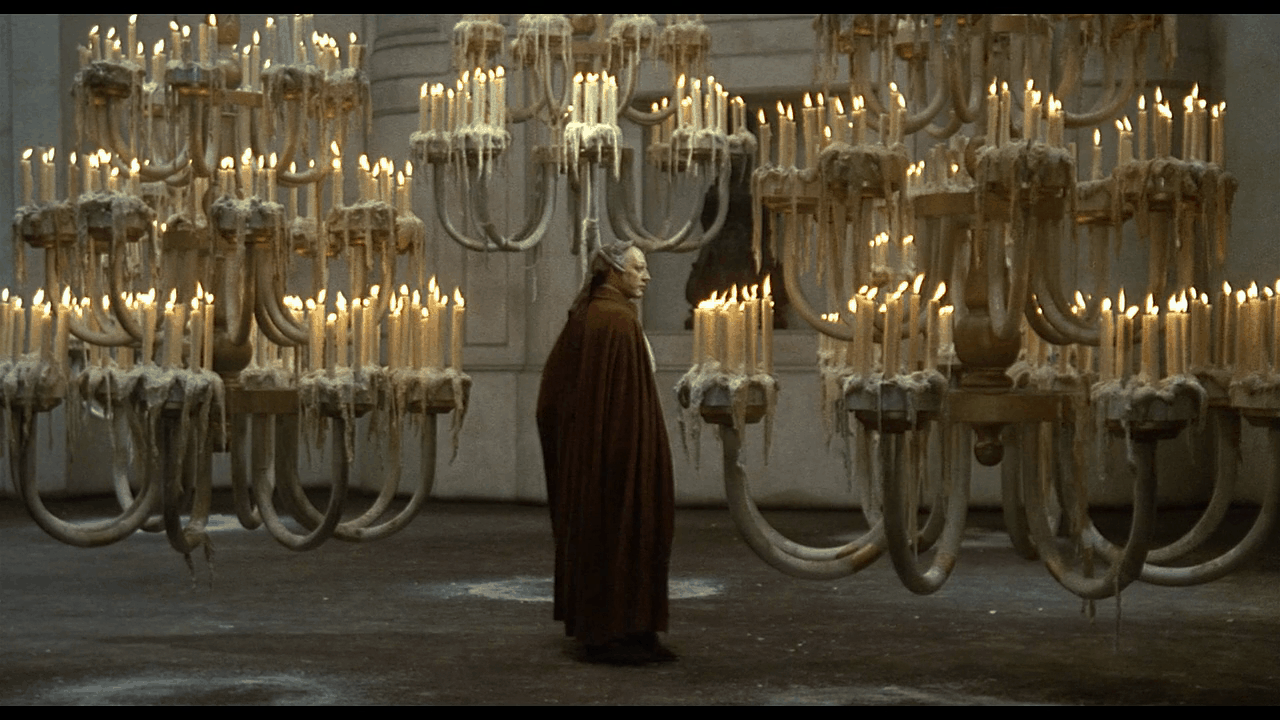

And speaking of brutal. In 1973 came

Thriller: A Cruel Picture,

probably Lindberg’s most famous film, the one film of hers most people

are at least somewhat aware of even if they don’t know who she is, and

one of the most controversial films ever made. It is also somewhat

complicated in terms of Lindberg’s filmography. On the one hand, the

film is, as its title states, quite the cruel picture. The inserted

shots of graphic sex surely stand out, as does some of the violence, the

most cringe-worthy example being the on-screen piercing and off-screen

removal of Lindberg’s character’s eye (the filmmakers actually used the

real eye of a corpse). It should be pointed out, however, that the

hard-core shots do not involve Lindberg. Contributing to her move away

from acting toward the end of the 1970s was her rather admirable refusal

to partake in straight pornography. Full frontal nudity was one thing,

explicit sex was another, so stand-ins were used for the close-ups (and

they are close up).

Thriller really stands alone in Lindberg’s body of work. If

one can get by the unnecessary explicitness of these pornographic

inserts, this is a classic 1970s revenge film, one of the best. Part of

the reason it is so memorable is that Lindberg’s Frigga is horribly

brutalized in just about every way imaginable, so by the time she does

enact her sweet retribution, a lot of people have a lot coming to them.

Frigga is first raped as a child, the trauma of which leaves her mute.

She is then drugged, given heroin to the point of dependency, held

hostage, forced into sex-slave labor, physically abused, and emotionally

tormented. When she is eventually able to leave for a few hours, she

secretly trains in hand-to-hand combat, firearms, and race car driving

(Lindberg really did learn karate for the role, and as she did not have a

driver’s license, she had to learn how to do that, too). Finally, the

time comes. Frigga assembles a stockpile of weaponry, dresses in black

from head to toe (including eye-patch), and embarks on a rigorous,

blood-spattered rampage. The low angle shot of this angelic beauty

turned kill-crazy vehicle for vengeance—adorned in a flowing black

trench coat, guns in hand, leaves falling around her—is one of the

greatest single images in all of Lindberg’s work. Hell, in all of

cinema.

Thriller was actually the first Christina Lindberg film I

had ever seen, about 10 years ago. I had no idea at the time who she was

and only watched the film because of its reputation and because

Lindberg’s patched eye was an inspiration for Daryl Hannah’s character

in

Kill Bill. Seeing it now as a showcase for one of Lindberg’s

most complex performances, and one of her most enjoyable, all those

other elements fade away. Its Tarantino-approved popularity is partly

why it is also hands-down the Lindberg film in the best condition. No

other DVD of her movies looks or sounds this good.

In films like

Schoolgirl Report Vol. 4 and

Secrets of Sweet Sixteen (1973),

Lindberg had relatively smaller roles in multi-part compendium

features, which told a variety of sexy stories usually dealing with

promiscuous young nubiles. Full disclaimer, I have not watched any of

the segments of any of these films if they did not contain Lindberg, and

therefore can’t judge any of these titles as a whole. In terms of what I

look for and enjoy in a Chistina Lindberg movie, however,

Secrets of Sweet Sixteen is just so-so (Lindberg is there, looking great, but the film and her specific character aren’t terribly interesting), but

Schoolgirl Report

certainly has its moments. There she looks even better, and while the

story of her character’s incestuous relationship with her brother may be

a bit off-putting, it’s a reasonably entertaining segment. Besides, if

nothing else, as the DVD proclaims, it also has “psychedelic dreams with

bloody naked nuns and a firing squad.” So, there’s that.

Lindberg’s last great featured role was in

Anita: Swedish Nymphet (1973). Not quite to the violent degree of

Thriller,

Anita

still has one of her darker characterizations. Interesting about this

film is that it is one where her sexuality figures into the essential

plot of the film; rather than just being a film that features a lot of

sex, this film is actually about sex. Lindberg plays, as the title

suggests, a 17-year-old nymphomaniac. Her insatiable sexual quest leads

her down a dark road of despair where she is ostracized and tormented by

a lack of self-worth. Somewhat in opposition to those films where

Lindberg is the submissive, mistreated girl, here she has an aggressive

sexuality that leaves her on the comparatively forceful end of her

amorous meetings. Yet through it all, she remains pathetic and

psychologically weak, chiefly because she is burdened by an inner

turmoil that does not, in most cases, make the sex pleasurable. It is

more a stolid routine that corresponds to the nature of addiction.

Certainly, Anita’s sexual promiscuity is exploited in the film, but

only to a degree (like when she performs a striptease in front of her

parents and their dignified houseguests, many of whom encourage the

routine—“It’s not as bad as it looks,” her father assures her stunned

mother). As often as not, the affliction is actually treated with a

reasonable seriousness, especially as Anita’s sole friend, Erik (a young

Stellan Skarsgård), tries to explain and “cure” her illness,

approaching her with sympathy and understanding. As far as Lindberg’s

performance is concerned, her expressed nymphomania, as dismissive as

one might be to the malady, gives her some psychological complexity to

work with, further proving there is genuine talent behind the doe-eyed

beauty. She quite capably conveys Anita’s desperation with a pitiable

quality reflected by the film itself, which is gloomy and generally

joyless. Anita, like the movie, has the look of a cold morning after.

What this does, and one sees this is several Lindberg films, especially

those where she is treated poorly, is it creates a sense of viewer

engagement beyond the frivolity of the film’s nature. One sees this poor

girl, this small, cute, seemingly helpless individual, and one can’t

help but want to comfort her.

Of everything that came after this for Lindberg, I have only seen

Around the World with Fanny Hill and

Sängkamrater (Wide Open),

both released in 1974. There isn’t a whole lot to say about these two

films, as Lindberg does not have much of a presence in the former and

only first appears 20 minutes into the latter, popping up infrequently

and marginally thereafter (though her first big scene is definitely

striking, by which I mean she gets very naked). In any case, for the

last two major films of Lindberg’s career, both are unfortunately rather

unremarkable.

Christina

Lindberg was the perfect actress at the right time for a certain kind

of movie. While this helped give her a briefly noteworthy career in the

1970s and she is something of a cult figure today, I can’t help but feel

her status in her respective field was and remains a hindrance. In most

sexploitation fare, the actors are there to do what they do and to do

little else, which is fine. Those movies and those performers have their

place in cinema history and this isn’t to belittle the work. But many

of these actors are seldom able to rise above the common filmic

territory (save for someone like Skarsgård). When watching Lindberg,

there appears to be a sincerity running counter to the triviality of the

films, and a talent, or at least the potential for talent, that has

been left underexplored and underrated because of the type of movies in

which she appeared. Her films are not “great” by any means, and I

definitely would not suggest her acting range was in any way

overwhelming. But if qualifications for being a memorable and enjoyable

star include leaving a strong impression no matter the size of the role

and making even a lesser movie better, she more than fits the bill.

Still, her acting isn’t terrible, especially for what she has to do

and what she had to work with. One of the defining traits of Lindberg’s

work is the impression that even she knows she is better than what she’s

dealing with. While most everyone else in these films seem to be

phoning in their performances, not trying too hard, perhaps knowing what

type of movie they’re making after all, Lindberg acts with an

earnestness that transcends her role and the material. This even seems

to be the case with her bigger-name co-stars, like Ulla Sjöblom, who in

1958 starred in Ingmar Bergman’s

The Magician, and Heinz Hopf, who had quite the television career before starring as villainous characters in

Exposed and

Thriller (and later also working with Bergman on

Fanny and Alexander). “When I worked I was very serious,” Lindberg said. “I tried to do my best.”

For all intents and purposes, Lindberg’s short-lived acting career

was nearing its end before she was 30 years old (an even shorter singing

career yielded just two songs). She started studying journalism soon

thereafter, wrote a number of articles for several publications, and

began working for her soon-to-be fiancé Bo Sehlberg at his aviation

magazine Flygrevyn, which she took over as owner and editor-in-chief

following his death in 2004. As her IMDb biography sums up, she is today

“a keen mushroom picker… an animal rights activist, an

environmentalist, and a vegetarian.”

During a few glorious years in the 1970s, though, Christina Lindberg was really something else.